In 1992, Nim Bahadur Magar left his village with very little.

One small bag.

Just a few rupees.

A big dream.

Nim was the eldest of six children — three sisters and three brothers — and there were no real job prospects waiting for him at home. What he did know was this: if there was any chance of working on rivers, it would be found in Kathmandu, where the rafting companies had their main offices.

Before leaving, Nim’s older sister gave him 320 rupees — money she had earned herself by selling local raksi. That was all he carried.

Wearing haati chaap chapal, a pair of jeans, and a hoodie, Nim crossed the river alone in a dugout canoe. From there, he waved down a local bus heading to the capital. The journey of roughly 200 kilometres took five hours, carrying him away from village life and toward something unknown.

Kathmandu, 1992

The big city.

A new beginning.

Kathmandu was overwhelming — louder, faster, and unfamiliar. Nim arrived with no job lined up and nowhere to stay. What he did have was the name of a river guide, Subhe, whom he had met earlier on the riverbank near his village.

Kathmandu was overwhelming — louder, faster, and unfamiliar. Nim arrived with no job lined up and nowhere to stay. What he did have was the name of a river guide, Subhe, whom he had met earlier on the riverbank near his village.

Finding Subhe in the city proved to be the turning point.

Through that connection, Nim was introduced to Osprey Waterways, where he was given a chance — not as a guide, but as a river guide trainee.

At Osprey, Nim trained under Osta Maharjan, a senior guide known for his discipline and high standards. Those early lessons — about patience, responsibility, and respect for the river — left a lasting impression and shaped Nim’s approach long before he ever led clients himself.

The company was owned by Udaya Man Sherchan, whose willingness to give young Nepali trainees opportunities played a significant role in the early development of Nepal’s rafting industry.

Learning Before the River

The early days were not glamorous.

Nim was allowed to sleep in the company warehouse. His mornings began with opening and cleaning the office, followed by long days maintaining, repairing, and cleaning equipment. The work was repetitive and physical. The river — the thing that had drawn him to Kathmandu — remained out of reach for a long time.

Slowly, Nim’s work ethic earned trust.

He was formally hired and began receiving a monthly salary of 400 rupees. With that, he moved out of the warehouse and into shared accommodation with other guides.

River days were rare at first. When they did come, Nim earned an additional 20 rupees per day. It wasn’t the money that mattered most. Each river day meant learning, observing, and slowly becoming part of the profession he had set out to enter.

This was a golden opportunity — not for comfort or quick success, but for training. Nim’s goal was clear: to learn as much as he could and eventually earn his government river guide license, allowing him to continue his journey professionally.

A Turning Point: 1995

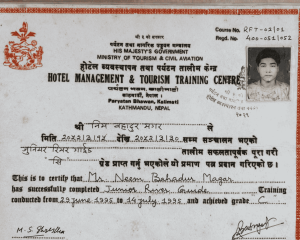

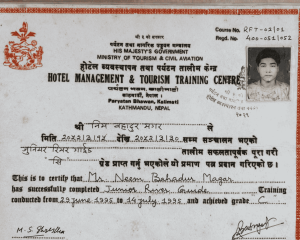

In 1995, after years of learning, working, and waiting patiently for every opportunity to be on the river, Nim completed and passed his government river guide licensing program, provided through Nepal’s official hotel management and tourism training system.

The license was more than a certificate. It was recognition — proof that the long days cleaning equipment, sleeping in warehouses, and earning trust slowly had led somewhere real.

The learning did not stop there.

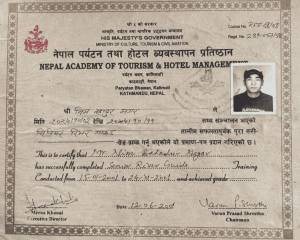

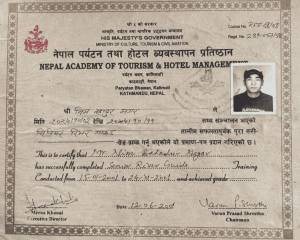

In 2001, Nim went on to achieve his government senior river guide license — a level that recognised not just technical skill, but experience, judgment, and responsibility on the river.

In 2001, Nim went on to achieve his government senior river guide license — a level that recognised not just technical skill, but experience, judgment, and responsibility on the river.

By then, guiding was no longer just work.

It was a craft, a profession, and a commitment.

Full Circle

Years later, that story came full circle.

Today, Nim is an instructor for the same government river guide training program, helping train and certify the next generation of Nepali river guides — just as he once was.

Just last week, Udaya dai visited Nim in Pokhara — a quiet reminder of how small and interconnected Nepal’s river community remains, and how relationships formed in the early days continue long after the work itself has changed.

This was not yet Paddle Nepal.

But the foundations were firmly in place.

This reflection is part of Paddle Nepal’s 20-year journey on Nepal’s rivers.

Kathmandu was overwhelming — louder, faster, and unfamiliar. Nim arrived with no job lined up and nowhere to stay. What he did have was the name of a river guide, Subhe, whom he had met earlier on the riverbank near his village.

Kathmandu was overwhelming — louder, faster, and unfamiliar. Nim arrived with no job lined up and nowhere to stay. What he did have was the name of a river guide, Subhe, whom he had met earlier on the riverbank near his village.

In 2001, Nim went on to achieve his government senior river guide license — a level that recognised not just technical skill, but experience, judgment, and responsibility on the river.

In 2001, Nim went on to achieve his government senior river guide license — a level that recognised not just technical skill, but experience, judgment, and responsibility on the river.